Majestically, he sat in authority over all that breathes and lifeless. While he lived, he was the soul and mind of his kingdom and was believed to be the deity’s representative on earth. His subjects held him sacrosanct. When he slept, the dominion with him slept until he woke up. He exercised the power of life and death over his subjects. Everyone, slaves and freeborns inclusive, was at his beck and call. At the snap of his fingers, he got unfettered access to anything he desired under the sun. He was omnipresent. With an extensive network of intelligence personnel, he had his eyes and ears in every private and public space. His inanimate royal staff of office, wherever it found itself, symbolized authority and ruled in his absence. His arrival was heralded by town criers, trumpeters, and royal guards. He patrolled his dominion and visited his fiefs flanked by armed horsemen, with a cavalry of death messengers on their heels. An aura of power, awe, and reverence surrounded him and his royal procession wherever they went. He was the temporal ‘alpha and omega’. Everything started and ended with him. Such was the awesomeness of the king’s supremacy before the advent of colonialism in Nigeria, and Africa in general.

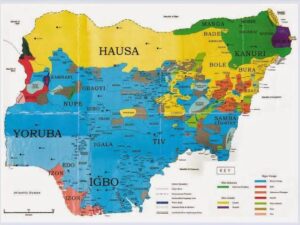

Majestically, he sat in authority over all that breathes and lifeless. While he lived, he was the soul and mind of his kingdom and was believed to be the deity’s representative on earth. His subjects held him sacrosanct. When he slept, the dominion with him slept until he woke up. He exercised the power of life and death over his subjects. Everyone, slaves and freeborns inclusive, was at his beck and call. At the snap of his fingers, he got unfettered access to anything he desired under the sun. He was omnipresent. With an extensive network of intelligence personnel, he had his eyes and ears in every private and public space. His inanimate royal staff of office, wherever it found itself, symbolized authority and ruled in his absence. His arrival was heralded by town criers, trumpeters, and royal guards. He patrolled his dominion and visited his fiefs flanked by armed horsemen, with a cavalry of death messengers on their heels. An aura of power, awe, and reverence surrounded him and his royal procession wherever they went. He was the temporal ‘alpha and omega’. Everything started and ended with him. Such was the awesomeness of the king’s supremacy before the advent of colonialism in Nigeria, and Africa in general. Fast-forward to the colonial era, a major shift occurred in the political power dynamics. The purveyors of Western imperialism had conquered the African kings. They had been reduced to proxies of new masters – the colonial authorities. They exercised authority at the behest of the District Officers having sworn allegiance to the Queen of England. They remained on the throne as long as they made the queen a happy woman. Recalcitrant kings who failed to fall in line were dethroned and exiled. Those who attempted to wage a war of resistance were brutally repressed, captured or killed. Such were the fates of King Jaja of Opobo in 1887, King Overawen of the Benin Kingdom in 1897, King Kosoko of Lagos in 1851, Emir of Bauchi, Umar Mohammed in 1902, Emir of Kano, Aliyu Karofi in 1903, and a host of others who dared to confront the authority of the new master. But with the wave and pressure of agitations for freedom in colonial territories worldwide, popular statements about the transience of power proved not to be just some threadbare clichés. As the air of freedom began to blow across the British colonial empire, the British government’s hold on political and administrative powers in Nigeria was finally relinquished on October 1st, 1960. Unfortunately for traditional rulers from whom power was originally wrested, power was not returned to them by the colonial masters. Instead, it was handed over to a new government elected by the people in line with the British government’s Westernization and democratization agenda. Since then, it became obvious that the traditional rulers would never be allowed to rule again, but would only be allowed to reign.

Without an iota of doubt, the subjugation of traditional monarchies by Western imperialists and the subsequent constitutionalizing of democratic rule have assigned new roles and responsibilities to the earthly gods who once bristled the land of the Niger. Since the Colonialists displaced them from a position of absolute authority, the traditional rulers have continued to see their powers whittled down by a succession of military and democratic rulers. Their powers have lately been so reduced that the the process by which they once ascended their thrones continues to be interfered with by vested interests, mostly, the modern-day governments. Also, in some quarters, they are perceived to have outlived their importance and are seen as anachronistic in contemporary societies. Some have even questioned modern-day governments’ decision to retain the institution of kingship despite its seeming redundancy in modern power dynamics. But undeterred by the relegation of their traditional authorities to the background, the inalienability of primordial cultural sentiments coupled with the symbolic connotation of the throne in African ontologies, made it impossible for any temporal power to abolish the institution into oblivion.

Be as it may, in many Nigerian Kingdoms today, the people are still so attached to and bound by their traditions and traditional rulers to the degree that the latter’s suggestions, advice, admonitions, and pronouncements on traditions, still influence their decisions. Interestingly, just as the people now occupy the central and cardinal positions within the newly introduced democratic order, so are the traditional rulers considered by modern-day governments to be veritable agents of grassroots political sensitization and mobilization due to the influence they can exercise over their people. Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that the long-established process by which the traditional rulers once ascended their thrones continues to be interfered with by vested interests. Far too often, modern-day governments and politicians eager to exploit their influence while attempting to rally support for their grassroots development programs and political ambitions leverage on the political influence of our traditional institutions.

Since the state governments are administratively closer to the people and deemed to have a better understanding of their culture and tradition, it is quite understandable why the Nigerian 1999 constitution, solely vested in the state governments the powers to legislate on matters relating to traditional institutions. The constitution also provides strictly consultative and advisory functions for the State Traditional Councils, a body that was also a creation of state laws. This residual power of the state governments transferred the regulatory functions hitherto exercised by the colonialists to the state governments. Associated with this power is the state governments’ responsibility to provide salaries and emoluments to the traditional rulers domiciled in their area of administrative authorities, the traditional rulers having lost their power to raise revenue through tax collection.

By now, Nigerians who pay rapt attention to happenings within their environments ought to have noticed many state governments’ dramatic creation and proliferation of monarchies in the last two decades. The truth is that communities that were once without or with only a few kings now parade scores of Kings who previously had no royal blood running through their veins. Likewise, many traditional chiefs whose ancestors were vassals under the authority of ancient kingdoms have now been elevated to kingships in those enclaves where their ancestors once functioned as subordinates or vassals. Expectedly, state governments have adduced reasons such as population explosion and progressive development to justify the proliferation of kingdoms. On the contrary, critics argued that the reasons cited are plausible. They contended that the state governments created new kingdoms and installed new kings to serve mainly as mobilization agents of politicians during electioneering. It is, however, remarkable that between June 2020 and May 2023, the Lagos State Government installed forty-eight Obas within its area of administrative authority. The Lagos state story is not so different from what is obtained in Oyo State and the rest of Southern Nigeria. Also in Northern Nigeria, many new emirates were created and many emirs were turbaned within the same period.

Similar to the events of the colonial period, traditional rulers deemed too powerful, disobedient or disloyal were dethroned and exiled by their state governors. In the same vein, between the time the colonial authorities transferred power to elected Nigerians and the present, scores of Kings have been removed from office by their state governors for offences ranging from political disloyalty to insubordination. That brings us to the ongoing ‘Royal Rumble’ in Kano state, a situation that has ignited a firestorm of controversy across the nation. Indubitably, the ongoing power tussle involving the current governor, some emirs and some subterranean political forces in Kano state has reduced the royal fathers to mere pawns in the political chess game. It all began with the former governor of the state, Abdullahi Ganduje appearing threatened by the sensational profile and personality of the Emir of the most important city in his state. Undoubtedly, only a man with an equally sound profile can afford not to be intimidated by the resume and achievements of a man who doubles as an emirate prince and a former Central Bank of Nigeria’s governor. Mr. Ganduje’s former boss and mentor, former governor Rabiu Kwankwanso who preceded Ganduje as Kano state governor shared this view. According to him, Ganduje is a man who “always feels diminished in the presence of the emir”. He also added that Ganduje “harbours a pathological hatred for the Kano traditional institution”.

On a critical assessment, the power imbalance between a traditional ruler and a governor attested to by Kwankwanso is quite untypical and a political aberration in constitutional democracies. It is crystal clear, that Emir Sanusi is not just an archetypal traditional ruler. In contrast, he has a personality that embodies great self-esteem, scholarship, intellectualism, professionalism, and a broad political influence. He is not the type a governor can manipulate or intimidate to do his bidding. Former Governor Ganduje must have found him ill-suited for his political agenda and had to let him go either by crook or by hook, an action seen widely by political analysts as authoritarian and oppressive. Ganduje subsequently created; a situation of dire portent in Kano state. But the transience of power once again manifested when two years after serving out his term of office, Ganduje’s political party was voted out, and a new governor was sworn into office. In a politically strategic move that shows that the tables have turned, the new Kano state governor, Abba Kabir Yusuf abolished the four emirates created by his predecessor in office, reverted to the old Kano emirate and reinstated Sanusi Lamido Sanusi as an Emir for the second time. As the saga continues, and a litany of judgements and counter-judgements emanate from different courts of law, the emirs have found themselves helplessly enmeshed in a cobweb of the politicians’ shenanigans. They have been precariously reduced to ordinary royal pawns in a tension-soaked political powerplay. If one thing is certain in the aftermath of the ongoing tussle, it is the realization that things will never be the same again. Victors will emerge and the vanquished will have their wounds to lick. The greatest fear and concern in all of these is what could finally befall the common man and the state of Kano.